|

|

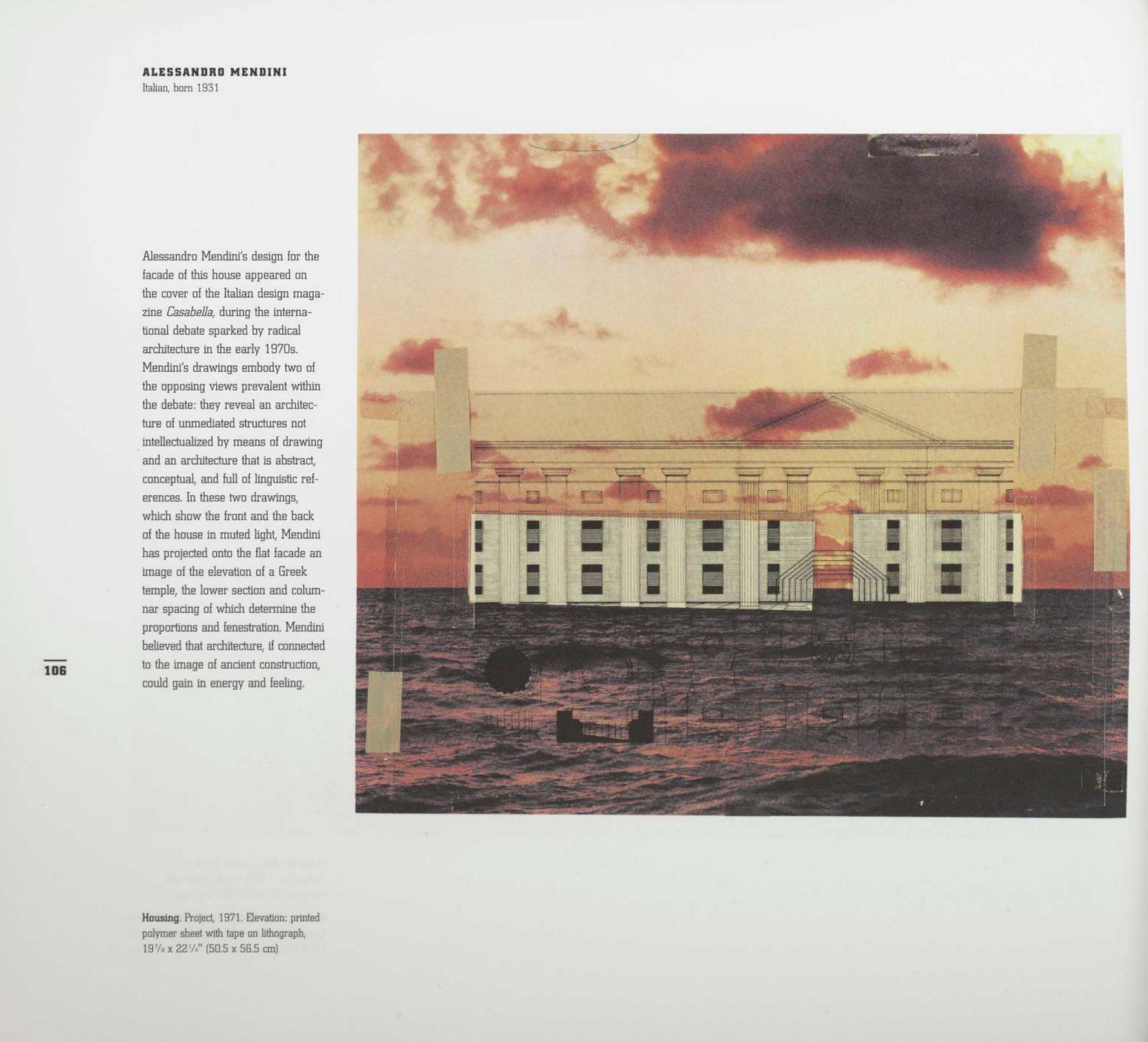

The changing of the avant-garde : Visionary architectural drawings from the Howard Gilman collection. — New York, 2002  The changing of the avant-garde : Visionary architectural drawings from the Howard Gilman collection / Contributions by Terence Riley, Sarah Deyong, Marco De Michelis, Pierre Apraxine, Paola Antonelli, Tina di Carlo, and Bevin Cline. — New York : The Museum of Modern Art, 2002. — 192 p. : ill. — ISBN 0-87070-004-9 (clothbound) ; ISBN 0-87070-003-0 (paperbound)

Along with its more than 200 lavish and beautifully reproduced architectural visions, this volume contains an introduction by Terence Riley, Chief Curator in the Department of Architecture and Design at the Museum, original essays on aspects of the Gilman collection by Sarah Deyong, Visiting Lecturer at the Pratt Institute School of Architecture, Brooklyn, New York, and Marco De Michelis, Professor of the History of Architecture and Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Instituto Universitario di Architettura, Venice; and an intriguing interview with the collection's curator, Pierre Apraxine.

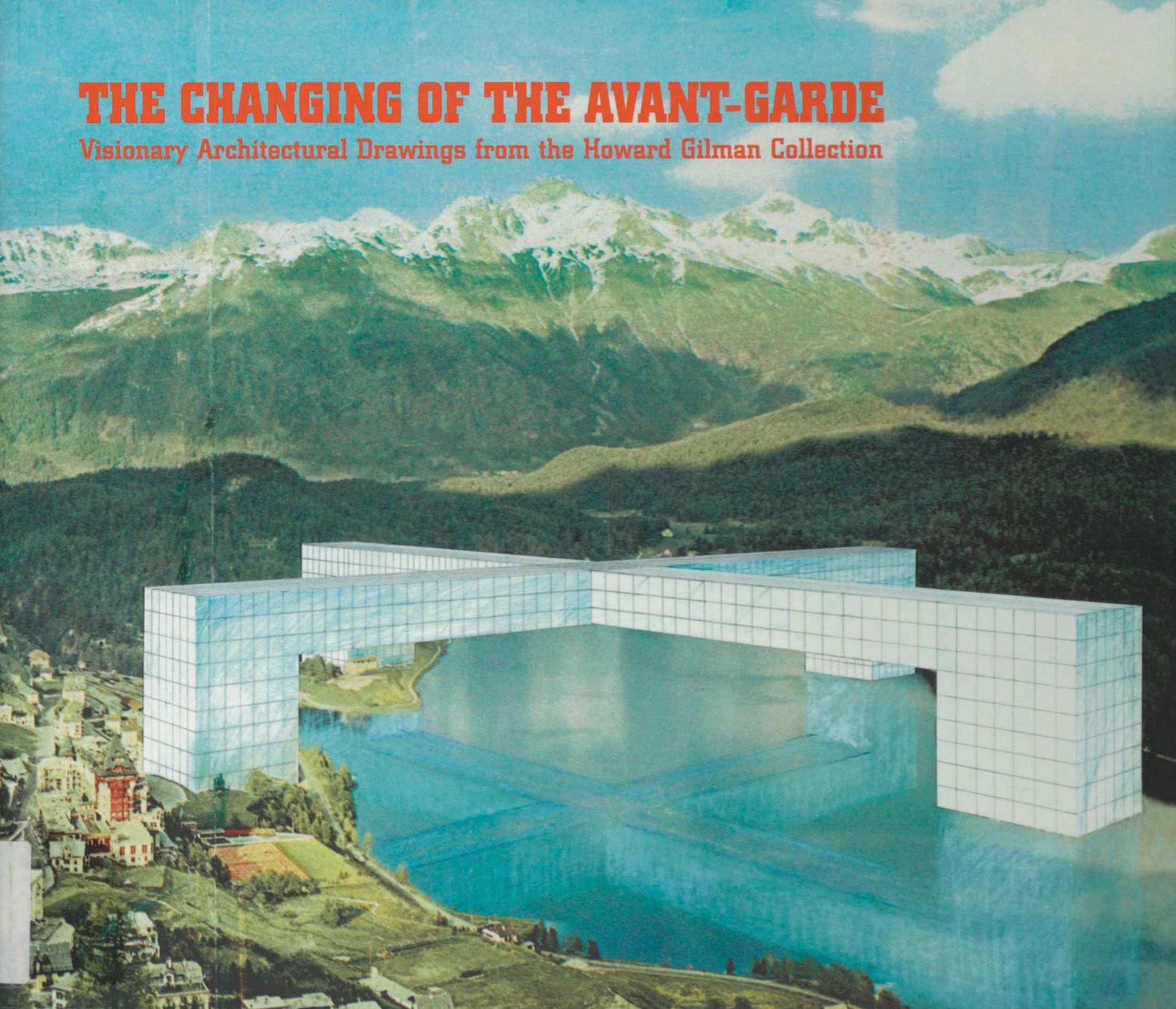

Front cover: Superstudio (Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, Gian Piero Frassinelli, Alessandro Magris, Roberto Magris, Adolfo Natalini). The Continuous Monument: St. Moritz Revisited. Project, 1969. Perspective: cut-and-pasted printed paper, color pencil, and oil stick on board.

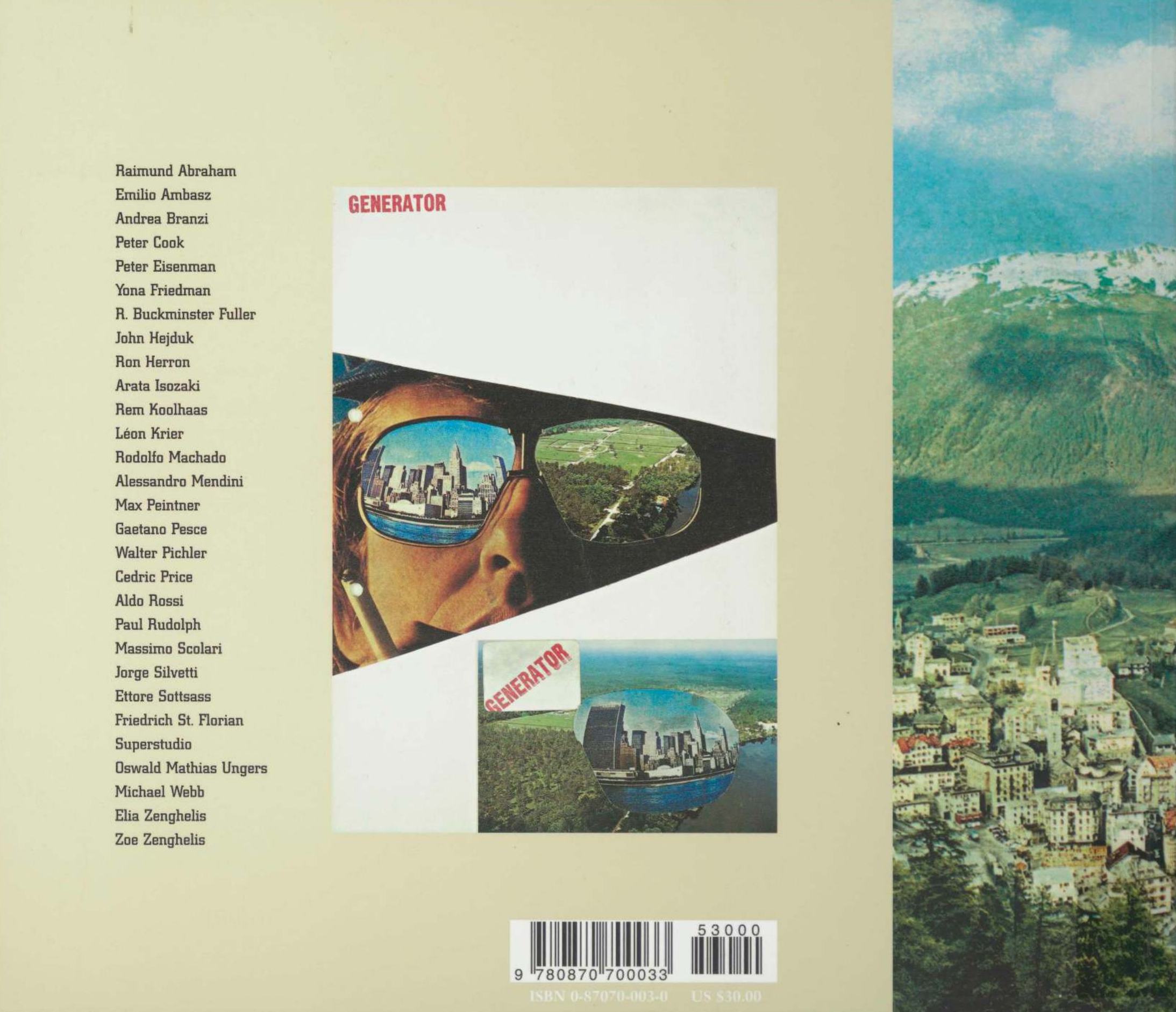

Back cover: Cedric Price. Generator, White Oak, Florida. Project, 1978–80. Untitled: cut-and-pasted printed papers with ink stamp on self-adhesive label, on paper with ink stamp.

The Howard Gilman Collection of Visionary Architectural Drawings includes some of the most famous utopian drawings of the twentieth century. Renowned among aficionados and scholars of radical architecture of the 1960s and 1970s for the quality and breadth of its content, the collection was generously donated to The Museum of Modern Art by The Howard Gilman Foundation in 2000. This volume celebrates the extraordinary bequest of the 205 spectacular artworks that comprise the gift, including renderings by some of the most respected architects of our time.

Taken together, the works represent a unique and fertile period in architecture and the world at large, especially during the radical political and social upheavals of the late 1960s. They provide a rare cross section of that era's rapidly changing currents, when a young generation of architects, involved in what came to be called the megastructure movement, sought to make a better world by ridding it of the exhausted modernist aesthetic of the prewar years. In its search for new paradigms and a fresh dynamic appropriate to postwar life and culture, this diverse group ultimately became the movement's most pointed critics. However, the brilliant visions they had along the way remain in their drawings.

The megastructuralists' objective emphasis on technology, flexibility, and comprehensive size gave way to an individualistic architecture of poetry, memory, and psychology expressed in smaller monuments, ruins, and postmodernist dreams of the future incorporating icons of the past. The Gilman collection's center of gravity is precisely at the moment of this transition, and includes key examples of the megastructure and early postmodernism, and also work by major figures who straddle both camps.

The forces unleashed by the demise of the megastructure and the advent of postmodernism remain vital creative forces in the world of architecture today. This volume's comprehensive view of a significant moment in history provides a unique window onto the root sources of present-day architectural practice.

CONTENTS

7 FOREWORD

Glenn D. Lowry

8 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

11 INTRODUCTION

Terence Riley

15 PLATES: PROLOGUE

23 MEMORIES OF THE URBAN FUTURE: THE RISE AND FALL OF THE MEGASTRUCTURE

Sarah Deyong

37 PLATES: THE MEGASTRUCTURE

89 ALDO ROSSI AND AUTONOMOUS ARCHITECTURE

Marco De Michelis

99 PLATES: POSTMODERN ROOTS

147 INTERVIEW WITH PIERRE APRAXINE

Paola Antonelli

155 PLATES: EPILOGUE

191 PHOTOGRAPH CREDITS

192 TRUSTEES

FOREWORD

On November 1, 2000, The Howard Gilman Foundation generously donated to The Museum of Modern Art one of the foremost collections of visionary architectural drawings in the world. The Howard Gilman Collection is renowned among scholars of the genre for the quality of the work and for the depth and breadth of its content. Focusing on radical projects from the 1960s and 1970s and comprising 205 artworks, the gift greatly enhances MoMA's existing holdings of visionary architectural drawings.

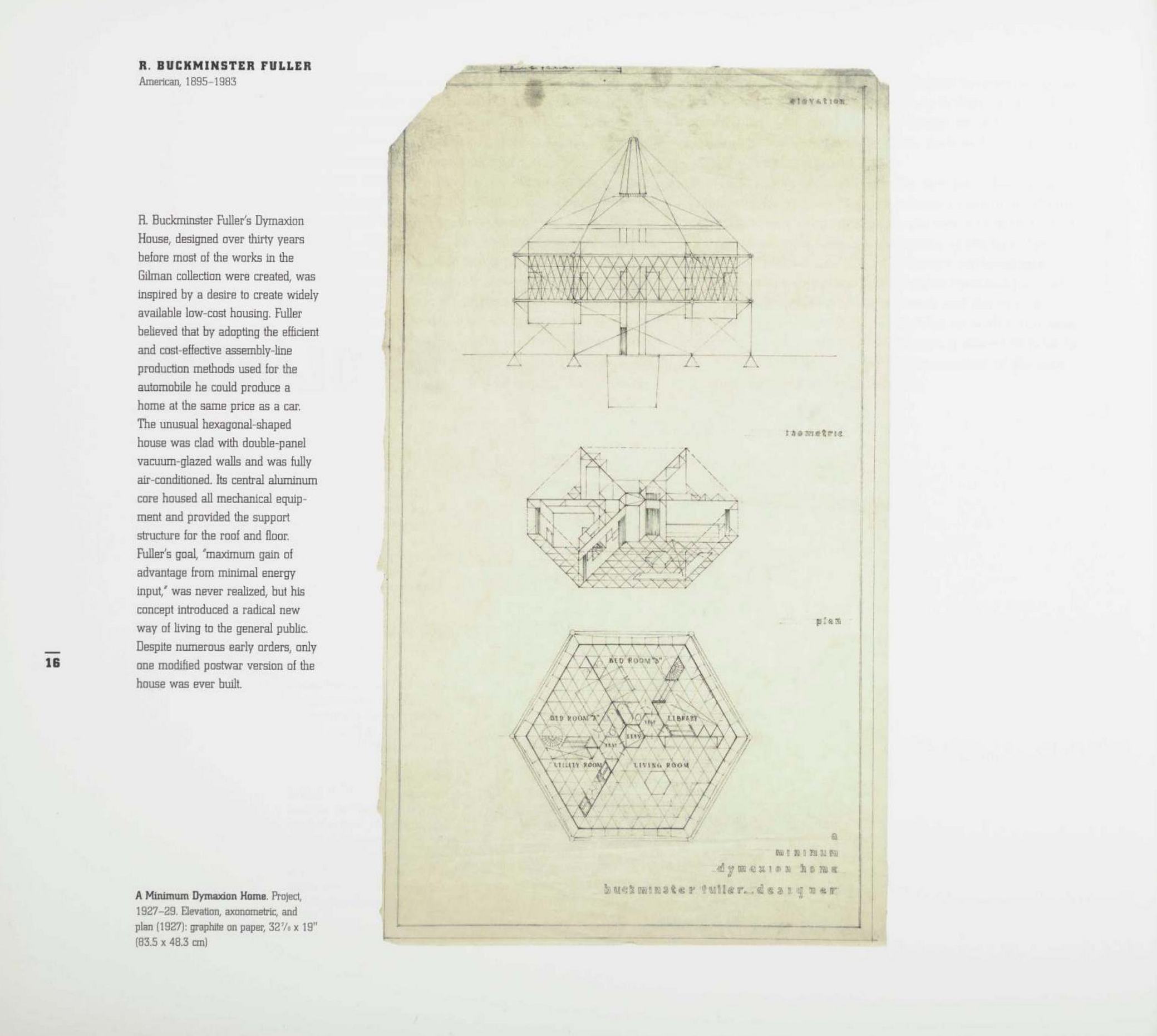

Included in the Gilman collection are some of the most famous utopian drawings of the twentieth century, such as R. Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion House of 1927-29 and Ron Herron's spectacular Cities : Moving of T964. Among the many architects whose work is featured in the collection are Raimund Abraham, Archigram, Arata Isozaki, Rem Koolhaas, and Ettore Sottsass. The acquisition of this collection led to the creation of the Howard Gilman Archive of Visionary Architectural Drawings, within the Museum's Department of Architecture and Design. The new archive now comprises the Gilman collection plus the Museum's existing holdings of visionary architectural drawings as well as future like-minded acquisitions.

On behalf of the Trustees and staff of the Museum, I wish to acknowledge a sincere debt of gratitude to the late Howard Gilman, The Howard Gilman Foundation, its officers and director, and to the curator of the Gilman collection, Pierre Apraxine, and his staff. To celebrate this extraordinary gift, Terence Riley, Chief Curator, Department of Architecture and Design has organized the exhibition, The Changing of The Avant Garde: Visionary Architectural Drawings from the Howard Gilman Collection, with the assistance of Tina di Carlo, Curatorial Assistant, Research and Collections, and Bevin Cline, Assistant Curator, Research and Collections. This publication documents the gift and the exhibition and also presents new scholarship on the period by Sarah Deyong and Marco De Michelis. The timeliness of this generous gift and the interest it has generated provide a unique moment to reflect on the generational shift that has so greatly affected the architectural culture of today.

Glenn D. Lowry

Director, The Museum of Modern Art

INTRODUCTION

Terence Riley

The visionary architectural drawings acquired by the New York art patron and collector Howard Gilman were assembled in just a few years, between 1976 and 1980, under the guidance of Pierre Apraxine, the collection's curator. Fortunately, their mutual interest in this field coincided with one of the great bursts of creative energy ever recorded on paper by architects, comprising nothing less than the last rally of the heroic visions of prewar modernism and the very first lights of what would broadly be known as postmodernism.

As a whole, the collection is not only unique, but is also a remarkably complete cross section of that period's rapidly changing currents in the world of architecture. But the prescience of Gilman and Apraxine is more than a matter of mere timing. As Apraxine says in an interview published in this volume, his having a certain distance from the profession of architecture may have benefited the selection: "I am actually a bit, not astonished, but intrigued by what this collection now represents... I think I had the kind of innocence that is needed to take a plunge into a field in which one is barely conversant... For me, everything is filtered through the senses, and the mind is there only to help."

In fact, it would have taken more than a little innocence of the architectural politics and personalities of the 1960s and 1970s to understand the fundamental unity that may occur when opposite poles are drawn together. In other words, from a certain perspective, the vision in visionary drawings can be seen as a continuous element of architectural expression, even when conflicting goals are at play.

"Make no small plans. They have no magic to stir men's blood," urged the architect and city planner Daniel Burnham in 1909, when he went before a committee evaluating his visionary proposal for replanning the city of Chicago. Burnham was speaking to a limited audience, but he might as well have been addressing the entire profession of architects who, from the outset of the twentieth century, would aspire to a scale of planning and building that would, indeed, stir men's blood—for good and for bad—for the next seventy-five years.

Of course, engineers preceded architects in grasping the potential scale of the Industrial Age, as can be seen in such grand nineteenth-century structures and public works as the Eiffel Tower and the Suez Canal. Inspired by these accomplishments, the quintessential avant-garde architect Le Corbusier peppered his pamphlets promoting modern architecture with pictures of ocean liners, grain elevators, and airplanes flying in formation. His Plan Voisin of 1925, which proposed leveling six hundred acres of the historic Marais district in Paris for his master plan of eighteen cruciform concrete towers, remains emblematic of the first marriage of visionary architecture and twentieth-century engineering.

If Le Corbusier is still referred to as a member of modernism's avant-garde, it is useful to remember the origins of that term in the military lexicon. The avant-garde was the expeditionary force, the leading edge amid the massed battalions. The effectiveness of such a force would depend on how thoroughly its individual members could focus their coordinated energies on a common objective. Indeed, Le Corbusier referred to a connexion des élites to describe his own disciplined vision of engineers, industrialists, politicians, and other professionals working together, not surprisingly, under the direction of the master architect, to achieve the twentieth century's goals.

From mid-century onward, there were plenty of examples to prove that thinking big was not in itself a guarantee of a big success. Many a comprehensive plan—New Towns in Great Britain, France, and elsewhere, urban renewal in America, and other grand schemes—produced not magic but big mistakes that seemed to defy remedy. In response, the 1960s saw a generation of architects—the Metabolists in Japan, Archigram in London, and loosely affiliated radicals in Italy and Austria—in open revolt against the values held dear by the modem establishment. Tellingly, their stinging critiques of postwar architecture and urbanism, and the visionary prewar foundations that preceded them, did not extend to modernism's embrace of the heroic scale of modem engineering. If anything, Archigram's Walking City by Ron Herron of 1966 (page 55) and Superstudio's The Continuous Monument project of 1969 (pages 73–77) trumped the scale of prewar architectural visions, and ushered in the megastructure movement, so well described in this volume by Sarah Deyong.

In megastructures a new generation saw potential for the transformation of culture and for making the post-1968 world a better one. Whereas Le Corbusier had looked to the ocean liner, younger voices were more influenced by the Beatles' Yellow Submarine, as the connexion des élites gave way to the values of the Woodstock Nation. Like Mao's Cultural Revolution, the megastructure movement sought to revive the dissipating energy of a once dynamic force. Although the megastructure movement shared none of the Cultural Revolution's fanatical methods, it did share the seeds of self-defeat in Marxism's dialectic of self-criticism. As Deyong clearly points out, the most ardent proponents of the megastructure ultimately became the movement's most pointed critics.

The implosion of the Cultural Revolution, as with the megastructure movement, opened the door for what Mao had described as the blossoming of a thousand flowers—the end of ideological orthodoxy and the validation of a broad search for new paradigms. Interestingly, a thousand blossoms of postmodern architecture would still be seen as an avant-garde force, if not a unified one, despite the collapse of the idea that its practitioners might share a common goal. In his interview, Apraxine says: "The only thing I knew at that time was that the modernist aesthetic was being questioned. But how it would change, really, nobody knew. I could feel a general disaffection with the exhausted idiom of conventional modernism. I knew there were reactions occurring; they were uncoordinated, but all were related by what they were trying to tear down."

In 1980, just as Gilman was winding down his acquisition of architectural drawings, the architectural historian Paolo Portoghesi organized the first exhibition of architecture under the auspices of the Venice Biennale, the biannual international survey of contemporary art.¹ Many of the architects represented in the Gilman collection were shown there. The title of Portoghesi's catalogue text, "The End of Prohibitionism," might be seen as reflecting the same antipathy to orthodox modernism as fueled the rise of the megastructure movement, although his essay actually emphasizes the nascent movement that succeeded megastructures. Portoghesi wrote: "The return of architecture to the womb of history and its recycling in new syntactic contexts of traditional forms is one of the characteristics that has produced a profound 'difference' in a series of works and projects in the past few years, understood by some critics to be in the ambiguous but efficacious category of Postmodernism."²

____________

¹ Despite its relationship to the Venice Biennale, the Architecture Section has never followed a biannual schedule. Its origins are also somewhat disputed. In 1976, an exhibition of the work of European and American architects was organized by Vittorio Gregotti, which many people consider to be the first Venice architecture exhibition.

² Paolo Portoghesi, “La fine del proibizionismo“ in La Presenza del Passaic (Milan: Electa, 1980): 9: “La restituzione dell'architettura nel grembo della stotia e il riciclaggia in nuovi contest! sintattici di forme tradizionali è uno dei sintomi che hanno prodotto una ‘diffeienza’ profonda in una serie di opera e ptogetii di questi anni compresi da alcuni critici nell’ambigua ma efficace categoria del Postmoderno.“

While the term postmodern has come to be associated with the revival of traditional architectural styles and means of construction, in 1980 the term embraced diverse individuals who were, as Apraxine states, "related by what they were trying to tear down." The heterogeneity of the "ambiguous but efficacious" new movement is evident both in the Gilman collection as well as well as Portoghesi's curatorial selections. For example, the work of Aldo Rossi played a prominent role in the Gilman collection and in the Biennale, as did that of Rem Koolhaas, Léon Krier, and Arata Isozaki. Frank Gehry and Hans Hollein were the artistes manquées of the former but central to the latter. If Portoghesi saw postmodernism as a return to the "womb of history," the architects and the works selected for his Venice exhibition reflect a more promiscuous sense of history than the archeologically correct form of postmodernism we know today.

Despite the postmodernists' divergent trajectories over time, it was Aldo Rossi, discussed in depth in this volume by Marco De Michelis, who played the role of the pivotal figure to this diverse group. His ideas of urban rationalism, archaic historical forms, deep emotion, and cultural, rather than global, expression defined architecture for his generation. If, in the 1980s and later, Rossi's having opened the Pandora's box of modernism—history—helped usher in the architectural traditionalism now known as postmodernism, he himself was no historicist but, rather, an architect who deeply understood the role of memory in the built environment.

Indeed, works such as Rossi's Cemetery of San Cataldo at Modena of 1971-84 (pages 110–115) looked to the past as a source of rich architectural and cultural memory more than for specific historical forms to be purloined. Gaetano Pesce's Church of Solitude of 1974–77 (pages 131–133) appears as a literal excavation of urban archeology, revealing the layers of historical meaning in Manhattan's undercroft. In the same way, Rem Koolhaas produced a project for the Roosevelt Island Redevelopment of 1975 (page 144), although in this instance the history was closer to hand, that of Manhattan's own modern formation in the early twentieth century. Employing modern myths, much as Gothic sculptors wrought embellishments from the lives of the saints, Koolhaas's project builds the city as it captures its stirring metropolitan magic.

The principal distinction that separates the megastructuralists from the emerging postmodernists is the disappearance of the purportedly objective common ground upon which Le Corbusier's connexion des élites was presumed to operate. Into that vacuum streamed a deluge of poetry, psychology, and memory with a full complement of architectural manifestations: ruins, dreams, and monuments. The scale of the projects was altered radically as well; the megastructuralists' overarching desire to embody society itself in their structures gave way a new kind of visionary expression—that of the individual artist seeking cultural transformation through self-revelation. Not surprisingly, many postmodernists of this period returned to what Sigmund Freud might have called the autobiographical mode of architecture—the house. Orthodoxy had given way to gnosis; the avant-garde had turned inward.

The Gilman collection's center of gravity is to be seen precisely at the moment of this transformation. It not only includes key examples of the megastructure as well as early postmodernism, but work by a number of key figures who straddle both movements—Aldo Rossi, Friedrich St. Florian, and Raimund Abraham. As a whole, the collection not only reflects the innocence of its curator but the innocence inherent in Ponoghesi's definition of postmodernism, whose big tent could accommodate such disparate figures as Frank Gehry and Robert Venturi in the quest to find a way out of late modernism. Ironically, just as the Biennale was opening, the common cause of many of its participants was shaken when Philip Johnson—also featured in the Venice exhibition—appeared on the cover of Time magazine with a model of his AT&T Building in New York, with its neo-Chippendale crown. Effectively endorsing a less ambiguous and more explicit reading of Portoghesi's "womb of history," Johnson's imprimatur gave traditional postmodernism a firm boast toward becoming the official architectural style of the Reagan era. Moreover, the tilt toward a conventional view of history set the stage for the ensuing architectural polemics between so-called traditional postmodernists, such as Robert Stern and Robert Venturi, and those who might be called cultural or philosophical postmodernists, such as Rem Koolhaas and Peter Eisenman.

The forces unleashed by the demise of the megastructure movement and the advent of postmodernism remain vital creative forces in the world of architecture today, In view of this, The Museum of Modern Art's Howard Gilman Archive of Visionary Architectural Drawings is a unique and invaluable resource for understanding the genesis of these forces and the vectors of invention they launched. It provides us with a rare and comprehensive view of a significant moment in history and also with fundamental documentation of the root sources of our architecture today.

Sample pages

Download link (pdf; yandexdisk; 30.6 MB)

The electronic version of this edition is published only for scientific, educational or cultural purposes under the terms of fair use. Any commercial use is prohibited. If you have any claims about copyright, please send a letter to [email protected].

10 апреля 2024, 13:52

0 комментариев

|

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий